The Same Exact People Got to Us Yet Again and They Tossed Me Down a Fire Escape at the Age of 3

| |

| Appointment | March 25, 1911 (1911-03-25) |

|---|---|

| Time | 4:40 p.m. (Eastern Time) |

| Location | Asch Building, Manhattan, New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Coordinates | xl°43′48″North 73°59′43″Due west / 40.73000°N 73.99528°Due west / 40.73000; -73.99528 Coordinates: 40°43′48″N 73°59′43″W / 40.73000°N 73.99528°West / forty.73000; -73.99528 |

| Deaths | 146 |

| Non-fatal injuries | 78 |

The Triangle Shirtwaist Manufacturing plant fire in the Greenwich Hamlet neighborhood of Manhattan, New York City, on Saturday, March 25, 1911, was the deadliest industrial disaster in the history of the city, and i of the deadliest in U.S. history.[1] The burn down caused the deaths of 146 garment workers – 123 women and girls and 23 men[2] – who died from the burn down, smoke inhalation, or falling or jumping to their deaths. Near of the victims were recent Italian or Jewish immigrant women and girls aged 14 to 23;[three] [iv] of the victims whose ages are known, the oldest victim was 43-year-onetime Providenza Panno, and the youngest were 14-year-olds Kate Leone and Rosaria "Sara" Maltese.[5]

The manufacturing plant was located on the 8th, ninth, and 10th floors of the Asch Building, which had been congenital in 1901. Later renamed the "Brown Building", it still stands at 23–29 Washington Place near Washington Square Park, on the New York University (NYU) campus.[vi] The edifice has been designated a National Historic Landmark and a New York City landmark.[7]

Because the doors to the stairwells and exits were locked[1] [eight] – a common do at the time to prevent workers from taking unauthorized breaks and to reduce theft[9] – many of the workers could not escape from the burning building and jumped from the high windows. The fire led to legislation requiring improved factory safety standards and helped spur the growth of the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union (ILGWU), which fought for amend working weather condition for sweatshop workers.

Background [edit]

The Triangle Waist Visitor[10] mill occupied the 8th, 9th, and tenth floors of the ten-story Asch Building on the northwest corner of Greene Street and Washington Place, only east of Washington Square Park, in the Greenwich Hamlet neighborhood of New York City. Under the ownership of Max Blanck and Isaac Harris, the factory produced women's blouses, known every bit "shirtwaists". The factory commonly employed nearly 500 workers, mostly young Italian and Jewish immigrant women and girls, who worked nine hours a day on weekdays plus seven hours on Saturdays,[11] earning for their 52 hours of work between $7 and $12 a week,[nine] the equivalent of $191 to $327 a week in 2018 currency, or $three.67 to $6.29 per hour.[12]

Burn down [edit]

A horse-fatigued fire engine en route to the burning manufacturing plant

At approximately 4:40 pm on Saturday, March 25, 1911, as the workday was catastrophe, a fire flared up in a scrap bin nether one of the cutter's tables at the northeast corner of the 8th floor.[thirteen] The commencement fire alarm was sent at iv:45 pm by a passerby on Washington Place who saw fume coming from the 8th flooring.[14] Both owners of the factory were in attendance and had invited their children to the manufactory on that afternoon.[15]

The Fire Marshal ended that the likely cause of the fire was the disposal of an unextinguished lucifer or cigarette butt in a scrap bin containing two months' worth of accumulated cuttings.[16] Beneath the tabular array in the wooden bin were hundreds of pounds of scraps left over from the several chiliad shirtwaists that had been cut at that tabular array. The scraps piled up from the concluding fourth dimension the bin was emptied, coupled with the hanging fabrics that surrounded it; the steel trim was the only affair that was not highly flammable.[13]

Although smoking was banned in the factory, cutters were known to sneak cigarettes, exhaling the smoke through their lapels to avoid detection.[17] A New York Times article suggested that the burn may have been started by the engines running the sewing machines. A serial of articles in Collier's noted a design of arson among certain sectors of the garment manufacture whenever their detail product fell out of fashion or had backlog inventory in order to collect insurance. The Insurance Monitor, a leading industry journal, observed that shirtwaists had recently fallen out of fashion, and that insurance for manufacturers of them was "fairly saturated with moral hazard." Although Blanck and Harris were known for having had four previous suspicious fires at their companies, arson was non suspected in this case.[15]

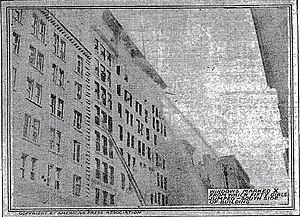

The edifice's southward side, with windows marked X from which l women jumped

62 people jumped or fell from windows

A bookkeeper on the 8th floor was able to warn employees on the tenth floor via telephone, but there was no audible warning and no way to contact staff on the 9th floor.[18] According to survivor Yetta Lubitz, the start warning of the fire on the ninth flooring arrived at the same time as the fire itself.[19]

Although the flooring had a number of exits, including two freight elevators, a burn down escape, and stairways downwardly to Greene Street and Washington Identify, flames prevented workers from descending the Greene Street stairway, and the door to the Washington Place stairway was locked to prevent theft by the workers; the locked doors immune managers to check the women's purses.[twenty] Diverse historians have likewise ascribed the get out doors beingness locked to management'southward wanting to keep out wedlock organizers due to direction's anti-union bias.[21] [22] [23] The foreman who held the stairway door key had already escaped past another road.[24] Dozens of employees escaped the burn past going up the Greene Street stairway to the roof. Other survivors were able to jam themselves into the elevators while they continued to operate.[25]

Within three minutes, the Greene Street stairway became unusable in both directions.[26] Terrified employees crowded onto the single exterior fire escape – which metropolis officials had immune Asch to erect instead of the required third staircase[13] – a flimsy and poorly anchored iron structure that may have been broken earlier the fire. Information technology soon twisted and collapsed from the oestrus and overload, spilling about twenty victims nearly 100 anxiety (30 thousand) to their deaths on the concrete pavement below. The remainder waited until smoke and burn down overcame them.

The burn down department arrived quickly but was unable to stop the flames, as their ladders were but long enough to reach equally high as the seventh floor.[1] The fallen bodies and falling victims also made it difficult for the fire section to arroyo the building.

Elevator operators Joseph Zito[27] and Gaspar Mortillaro saved many lives by traveling three times up to the 9th floor for passengers, but Mortillaro was somewhen forced to give up when the rails of his elevator buckled under the estrus. Some victims pried the elevator doors open and jumped into the empty shaft, trying to slide down the cables or to land on elevation of the car. The weight and impacts of these bodies warped the lift car and made it impossible for Zito to make another attempt. William Gunn Shepard, a reporter at the tragedy, would say that "I learned a new audio that day, a sound more horrible than clarification can picture – the thud of a speeding living trunk on a rock sidewalk".[28]

A big crowd of bystanders gathered on the street, witnessing 62 people jumping or falling to their deaths from the burning building.[29] Louis Waldman, after a New York Socialist state assemblyman, described the scene years later:[30]

One Sabbatum afternoon in March of that twelvemonth – March 25, to be precise – I was sitting at one of the reading tables in the erstwhile Astor Library. … It was a raw, unpleasant day and the comfortable reading room seemed a delightful place to spend the remaining few hours until the library airtight. I was securely engrossed in my book when I became aware of fire engines racing by the edifice. Past this time I was sufficiently Americanized to exist fascinated by the audio of fire engines. Forth with several others in the library, I ran out to see what was happening, and followed crowds of people to the scene of the burn.

A few blocks away, the Asch Edifice at the corner of Washington Place and Greene Street was ablaze. When we arrived at the scene, the law had thrown up a cordon around the area and the firemen were helplessly fighting the blaze. The 8th, 9th, and tenth stories of the building were now an enormous roaring cornice of flames.

Word had spread through the Due east Side, past some magic of terror, that the plant of the Triangle Waist Company was on fire and that several hundred workers were trapped. Horrified and helpless, the crowds – I among them – looked up at the called-for building, saw girl after daughter appear at the reddened windows, pause for a terrified moment, so leap to the pavement below, to country equally mangled, bloody pulp. This went on for what seemed a ghastly eternity. Occasionally a girl who had hesitated as well long was licked by pursuing flames and, screaming with clothing and hair ablaze, plunged similar a living torch to the street. Life nets held by the firemen were torn past the impact of the falling bodies.

The emotions of the crowd were indescribable. Women were hysterical, scores fainted; men wept as, in paroxysms of frenzy, they hurled themselves against the law lines.

Bodies of the victims existence placed in coffins on the sidewalk

Backwash [edit]

Although early references of the death toll ranged from 141[31] to 148,[32] almost all modern references agree that 146 people died every bit a result of the burn down: 123 women and girls and 23 men.[33] [34] [35] [36] [37] [38] [39] Most victims died of burns, asphyxiation, edgeless impact injuries, or a combination of the three.[40]

The first person to jump was a man, and another man was seen kissing a young woman at the window earlier they both jumped to their deaths.[41]

Bodies of the victims were taken to Charities Pier (also called Misery Lane), located at 26th street and the Due east River, for identification by friends and relatives.[42] Victims were interred in sixteen different cemeteries.[33] 22 victims of the fire were buried past the Hebrew Free Burial Association[43] in a special section at Mount Richmond Cemetery. In some instances, their tombstones refer to the burn down.[44] Vi victims remained unidentified until Michael Hirsch, a historian, completed four years of researching newspaper articles and other sources for missing persons and was able to identify each of them past proper noun.[33] [34] Those six victims were buried together in the Cemetery of the Evergreens in Brooklyn. Originally interred elsewhere on the grounds, their remains now lie beneath a monument to the tragedy, a large marble slab featuring a kneeling adult female.[33] [45] [46]

People and horses draped in black walk in procession in memory of the victims

Consequences and legacy [edit]

The company's owners, Max Blanck and Isaac Harris – both Jewish immigrants[47] – who survived the fire by fleeing to the building's roof when it began, were indicted on charges of first- and second-degree manslaughter in mid-April; the pair's trial began on Dec 4, 1911.[48] Max Steuer, counsel for the defendants, managed to destroy the credibility of one of the survivors, Kate Alterman, by asking her to echo her testimony a number of times, which she did without altering key phrases. Steuer argued to the jury that Alterman and possibly other witnesses had memorized their statements, and might even take been told what to say by the prosecutors. The prosecution charged that the owners knew the get out doors were locked at the time in question. The investigation found that the locks were intended to exist locked during working hours based on the findings from the fire,[49] just the defense stressed that the prosecution failed to prove that the owners knew that.[ citation needed ] The jury acquitted the two men of first- and 2d-degree manslaughter, but they were found liable of wrongful death during a subsequent ceremonious suit in 1913 in which plaintiffs were awarded compensation in the corporeality of $75 per deceased victim.[50] [51] [52] The insurance company paid Blanck and Harris well-nigh $sixty,000 more than the reported losses, or about $400 per casualty.[53]

In 1913, Blanck was once more arrested for locking the door in his factory during working hours. He was fined $twenty which was the minimum corporeality the fine could be.[54]

Rose Schneiderman, a prominent socialist and union activist, gave a speech communication at the memorial meeting held in the Metropolitan Opera Business firm on Apr 2, 1911, to an audience largely made upwards of the members of the Women's Trade Union League. She used the fire as an argument for factory workers to organize:[55]

I would be a traitor to these poor burned bodies if I came here to talk practiced fellowship. Nosotros have tried yous good people of the public and we have plant you wanting… We have tried you citizens; we are trying y'all at present, and yous have a couple of dollars for the sorrowing mothers, brothers, and sisters by manner of a charity gift. Only every time the workers come out in the only way they know to protest confronting conditions which are unbearable, the strong hand of the law is allowed to printing down heavily upon u.s..

Public officials take only words of warning to us-warning that we must exist intensely peaceable, and they have the workhouse just back of all their warnings. The strong mitt of the police beats u.s. back, when we rising, into the weather condition that brand life unbearable.

I can't talk fellowship to you who are gathered here. Too much blood has been spilled. I know from my experience it is up to the working people to salve themselves. The merely manner they can save themselves is by a strong working-class movement.[56]

Others in the community, and in particular in the ILGWU,[57] believed that political reform could help. In New York City, a Commission on Public Rubber was formed, headed past eyewitness Frances Perkins[58] – who 22 years later on would be appointed United States Secretary of Labor – to identify specific problems and lobby for new legislation, such as the beak to grant workers shorter hours in a work week, known as the "54-hour Bill". The committee's representatives in Albany obtained the backing of Tammany Hall's Al Smith, the Bulk Leader of the Associates, and Robert F. Wagner, the Bulk Leader of the Senate, and this collaboration of machine politicians and reformers – besides known as "do-gooders" or "goo-goos" – got results, especially since Tammany'southward primary, Charles F. Murphy, realized the goodwill to be had as champion of the downtrodden.[ix]

The New York State Legislature then created the Factory Investigating Commission to "investigate mill conditions in this and other cities and to report remedial measures of legislation to prevent hazard or loss of life amid employees through fire, unsanitary weather condition, and occupational diseases."[59] The Commission was chaired by Wagner and co-chaired by Al Smith. They held a series of widely publicized investigations effectually the state, interviewing 222 witnesses and taking 3,500 pages of testimony. They hired field agents to practice on-site inspections of factories. They started with the outcome of fire safe and moved on to broader issues of the risks of injury in the factory surroundings. Their findings led to 30-viii new laws regulating labor in New York state, and gave them a reputation equally leading progressive reformers working on behalf of the working course. In the procedure, they changed Tammany's reputation from mere corruption to progressive endeavors to assist the workers.[60] [61] New York Metropolis'due south Fire Main John Kenlon told the investigators that his section had identified more than than 200 factories where conditions made a burn down like that at the Triangle Factory possible.[62] The Country Commissions'south reports helped modernize the land's labor laws, making New York State "one of the most progressive states in terms of labor reform."[63] [64] New laws mandated better edifice access and egress, fireproofing requirements, the availability of fire extinguishers, the installation of alert systems and automatic sprinklers, meliorate eating and toilet facilities for workers, and limited the number of hours that women and children could work.[65] In the years from 1911 to 1913, sixty of the sixty-four new laws recommended by the Commission were legislated with the support of Governor William Sulzer.[9]

Every bit a effect of the fire, the American Society of Safety Professionals was founded in New York City on October 14, 1911.[66]

The last living survivor of the burn was Rose Freedman, née Rosenfeld, who died in Beverly Hills, California, on February 15, 2001, at the historic period of 107. She was two days away from her 18th altogether at the time of the fire, which she survived past post-obit the visitor'due south executives and being rescued from the roof of the building.[67] As a consequence of her feel, she became a lifelong supporter of unions.[68]

On September 16, 2019, U.S. Senator Elizabeth Warren delivered a spoken communication in Washington Foursquare Park supporting her presidential campaign, a few blocks from the location of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory burn down.[69] Sen. Warren recounted the story of the burn and its legacy before a crowd of supporters, likening activism for workers' rights following the 1911 fire to her ain presidential platform.[70] [71]

Remember the Triangle Fire Coalition [edit]

Hilda Solis, the American Secretary of Labor, seen on the overhead screen, speaking at the Centennial Memorial; the Brown (Asch) Edifice is on the far right.

The Remember the Triangle Fire Coalition is an alliance of more than 200 organizations and individuals formed in 2008 to encourage and coordinate nationwide activities commemorating the centennial of the fire[72] and to create a permanent public art memorial to honor its victims.[73] [74] The founding partners included Workers United, the New York City Burn down Museum, New York University (the current possessor of the building), Workmen'southward Circle, Museum at Eldridge Street, the Greenwich Village Society for Celebrated Preservation, the Lower Due east Side Tenement Museum, the Gotham Center for New York City History, the Bowery Poetry Club and others. Members of the Coalition include arts organizations, schools, workers' rights groups, labor unions, human rights and women'due south rights groups, ethnic organizations, historical preservation societies, activists, and scholars, as well as families of the victims and survivors.[75]

The Coalition grew out of a public fine art project called "Chalk" created by New York Urban center filmmaker Ruth Sergel.[76] Every year commencement in 2004, Sergel and volunteer artists went across New York City on the anniversary of the fire to inscribe in chalk the names, ages, and causes of death of the victims in front of their erstwhile homes, often including drawings of flowers, tombstones or a triangle.[72] [77]

Centennial [edit]

The commemoration drew thousands of people, many holding aloft "146 Shirtwaist-Kites" conceived past creative person Annie Lanzillotto and designed and made by members of The Remember the Triangle Burn Coalition, with the names of the victims on sashes, as they listened to speakers.

From July 2009 through the weeks leading up to the 100th anniversary, the Coalition served as a clearinghouse to organize some 200 activities as varied as bookish conferences, films, theater performances, fine art shows, concerts, readings, awareness campaigns, walking tours, and parades that were held in and around New York City, and in cities across the nation, including San Francisco, Los Angeles, Chicago, Minneapolis, Boston and Washington, D.C.[72]

The ceremony, which was held in front of the edifice where the fire took place, was preceded past a march through Greenwich Village past thousands of people, some conveying shirtwaists – women'southward blouses – on poles, with sashes commemorating the names of those who died in the burn. Speakers included the U.s.a. Secretarial assistant of Labor, Hilda 50. Solis, U.S. Senator Charles Schumer, New York City Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg, the actor Danny Glover, and Suzanne Pred Bass, the grandniece of Rosie Weiner, a young woman killed in the bonfire. Most of the speakers that twenty-four hours called for the strengthening of workers' rights and organized labor.[78] [79]

At 4:45 pm EST, the moment the start burn down alarm was sounded in 1911, hundreds of bells rang out in cities and towns across the nation. For this commemorative human activity, the Remember the Triangle Burn down Coalition organized hundreds of churches, schools, fire houses, and private individuals in the New York City region and across the nation. The Coalition maintains on its website a national map denoting each of the bells that rang that afternoon.[fourscore]

Permanent memorial [edit]

The Coalition has launched an attempt to create a permanent public fine art memorial for the Triangle Shirtwaist Manufactory fire at the site of the 1911 burn in lower Manhattan. In 2012, the Coalition signed an agreement with NYU that granted the organisation permission to install a memorial on the Brown Building and, in consultation with the Landmarks Preservation Commission, indicated what elements of the building could be incorporated into the design. Architectural designer Ernesto Martinez directed an international contest for the design. A jury of representatives from fashion, public fine art, design, architecture, and labor history reviewed 170 entries from more than 30 countries and selected a spare withal powerful blueprint past Richard Joon Yoo and Uri Wegman.[81] On Dec 22, 2015, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo announced that $1.5 million from country economical development funds would be earmarked to build the Triangle Burn down Memorial.[82]

The pattern of the memorial consists of a stainless-steel ribbon that cascades vertically down the corner of the Dark-brown Building (23-29 Washington Place) from the window-sill of the ninth floor, marking the location where most of the victims of the Triangle fire died or jumped to their death. The steel ribbon is etched with patterns and textures from a 300-foot long cloth ribbon, formed from individual pieces of material, donated and sewed together past hundreds of volunteers. At the cornice above the first flooring, the steel ribbon splits into horizontal bands that run perpendicularly along the eastward and due south facades of the building, floating twelve anxiety to a higher place the sidewalk. The names of all 146 workers who died will be laser-cut through these panels, allowing low-cal to pass through. At street level, an angled panel made of stone glass at hip height will reflect the names overhead. Testimonies from survivors and witnesses will be inscribed in this reflective panel juxtaposing the names and history.[83]

In 2011, the Coalition established that the goal of the permanent memorial would be:[ commendation needed ]

- To laurels the memory of those who died from the fire;

- To assert the dignity of all workers;

- To value women'southward work;

- To recollect the movement for worker safety and social justice stirred by this tragedy;

- To inspire future generations of activists

Mt. Zion Cemetery Memorial [edit]

A memorial "of the Ladies Waist and Dress Makers Union Local No 25" was erected in Mt. Zion Cemetery in Maspeth, Queens (twoscore°44'2" Due north 73°54'eleven" Westward). It is a series of stone columns holding a large cross beam. Much of the writing is no longer legible due to erosion.

In pop culture [edit]

Films and telly

- The Crime of Carelessness (1912), xiv-minute Thomas A. Edison, Inc., short inspired by the Triangle Manufactory fire, directed by James Oppenheim

- With These Hands (1950), directed by Jack Arnold

- The Triangle Factory Fire Scandal (1979), directed by Mel Stuart, produced past Mel Brez and Ethel Brez

- American Pop (1981), an developed animated musical drama motion-picture show written by Ronni Kern and directed by Ralph Bakshi features a scene taking place in the fire.

- Those Who Know Don't Tell: The Ongoing Battle for Workers' Health (1990), produced by Abby Ginzberg, narrated by Studs Terkel[84]

- Episode 4 of Ric Burns' 1999 PBS series New York: A Documentary Film, "The Ability and the People (1898–1918)", extensively covered the fire.

- The Living Century: 3 Miracles (2001) premiered on PBS, focusing on the life of 107-yr-old Rose Freedman (died 2001), who became the last living survivor of the burn.[68]

- American Feel: Triangle Burn down (2011), documentary produced and directed past Jamila Wignot, narrated by Michael Murphy[85]

- Triangle: Remembering the Burn (2011) premiered on HBO on March 21, four days curt of the 100th anniversary.[86]

- In season three episode 7 of SyFy Channel TV show Warehouse 13 (2011), characters Claudia Donovan and Steve Jinks recover an artifact from the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire, a doorknob which burns people.[87]

- In season 1 episode 4 of The CW TV sitcom Crazy Ex-Girlfriend, characters Rebecca Agglomeration and Greg Serrano are on an awkward first appointment, but then they start to bond after their shared interest in the Triangle Shirtwaist Manufactory Burn, with Greg calling it his "favorite fire." This foreshadows Rebecca'south past as an arsonist.

- The Fire of a Movement (2019) Episode of PBS series The Future of America's Past – "... We visit the building and larn how public outcry inspired workplace rubber laws that revolutionized industrial work nationwide. Descendants and activists prove us how that work reverberates today."[88]

Music

- "Dos hat fun nokh dem fayer"[89] ("The Song from afterwards the Fire") by Yiddish lyricist Charles Simon, 1912.

- "My Little Shirtwaist Fire" past Rasputina, from their 1996 album Thank you for the Ether.[90]

- "Die Fire Korbunes"[91] (The Fire Victims), music past David Meyerowitz, 1911

- "The Triangle Burn down" by The Brandos, from their 2006 album Over the Border.[92]

- "Sweatshop Fire" past Curtis Eller, from his 2008 anthology Wirewalkers and Assassins.[93]

- "Washington Square", by Si Kahn, from his album Courage [94]

- Fire in my mouth (2018),[95] a 60-minute oratorio for 146 female voices and orchestra by Julia Wolfe premiered past The Crossing (choral ensemble), The Immature People's Chorus of New York Urban center, and The New York Philharmonic under the management of Jaap van Zweden at David Geffen Hall, Lincoln Center on Jan 24, 2019.[96]

Theatre and dance

- Naomi Wallace's 1996 play Slaughter City includes a grapheme, the Fabric Worker, that was killed in the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire, and the play itself was inspired by several labor events throughout the 20th century, including the burn down.[97] [98]

- In Ain Gordon's play Birdseed Bundles (2000), the Triangle fire is a major dramatic engine of the story.[99]

- The musical Rags – volume by Joseph Stein, lyrics by Stephen Schwartz, and music by Charles Strouse – incorporates the Triangle Shirtwaist fire in the second human activity.[100]

- In March 2012, the mod trip the light fantastic toe concert 1 Hundred Forty-Six by Denise J. White potato explored the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory burn through motion, text, video, photography and original music.[101]

- Scintille ("Sparks") is a 2012 Italian political play by Laura Sicignano which centers on the fire and the circumstances surrounding it.[102]

- Triangle, a phase musical with music by Curtis Moore, lyrics past Thomas Mizer, and book past Thomas Mizer, Curtis Moore and Joshua Scher, deals with the Shirtwaist Manufactory burn down on the 100th anniversary of the tragedy through the optics of a scientist whose laboratory is located in the Asch Building. The play was premiered at TheatreWorks in Palo Alto, California in July 2015.[103]

- In their 2018 product of A Bintel Brief, a play chronicling the trials of Jewish immigrants to America at the turn of the 20th century, The Dora Wasserman Yiddish Theatre in Montreal, Canada, translated the songs "The Ballad of the Triangle Burn" and Bread and Roses into Yiddish for the beginning time. The world premiere of these new translations was released every bit a video in March 2020 to commemorate the anniversary of the fire.

Literature

- Triangle: The Fire That Changed America by David Von Drehle, 2003 (ISBN 978-0802141514)

- The Triangle Fire by Leon Stein, 1963 (ISBN 978-0801477072)

- Fragments from the Burn down: The Triangle Shirtwaist Company Fire of March 25, 1911, a volume of poesy past Chris Llewellyn, 1987 (ISBN 978-0140585865).

- Triangle, a 2006 novel by Katharine Weber (ISBN 978-0374281427), tells the story of the final living survivor of the fire, whose story hides the truth of her experience on March 25, 1911, raising the questions of who owns history and whose stories prevail.

- Margaret Peterson Haddix'southward 2007 historical novel for young adults, Uprising (ISBN 978-1416911715), deals with immigration, women'southward rights, and the labor movement, with the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire as a cardinal element.

- Esther Friesner's Threads and Flames (ISBN 978-0670012459) deals with a young girl, named Raisa, who works at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory at the time of the burn.

- Deborah Hopkinson's 2004 historical novel for immature adults, Hear My Sorrow: The Diary of Angela Denoto (ISBN 978-0439221610).

- Mary Jane Auch's 2004 historical novel for young adults, Ashes of Roses (ISBN 978-0-312-53580-3) tells the tale of Margaret Rose Nolan, a young girl who works at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory at the time of the fire, along with her sister and her friends.

- The comic book The Goon issue No. 37 tells the story of a like fire at a girdle factory that takes the lives of 142 women who worked there. Afterwards the burn down, the surviving women attempt to unionize and the Goon comes to their help after wedlock busters endeavor to forcefulness them back to work. Author Eric Powell specifically cites the Triangle Shirtwaist Mill fire every bit an inspiration for the story.[ commendation needed ]

- Vivian Schurfranz's novel Rachel (ISBN 978-0590403948), from the Sunfire serial of historical romances for young adults, is nearly a Smoothen Jewish immigrant daughter who works at the Triangle Shirtwaist Manufactory at the time of the burn down.

- Robert Pinsky's verse form Shirt describes the fire.[104]

- "Mayn Rue Platz" (My Resting Place), a verse form written past old Triangle employee Morris Rosenfeld, has been set up to music, in Yiddish and English, past many artists, including Geoff Berner[105] and June Tabor.[106]

- In Alice Hoffman's novel The Museum of Extraordinary Things (ISBN 978-1451693577), the fire is one of the main elements of the plot.

- "Afterlife", a 2013 brusque story by Stephen Male monarch, centers effectually Isaac Harris in Purgatory talking well-nigh the burn down.[ citation needed ]

- In a section of Edward Rutherfurd's novel New York (ISBN 978-0385521383), a protagonist'southward sis, from an Italian immigrant family, dies after jumping from a window to escape the fire.

- Sholem Asch's 1946 novel Eastward River (ISBN 978-1432619992) tells the story of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire through the eyes of an Irish girl who was working at the factory at a time of the fire.

- Helene Wecker's 2021 novel The Subconscious Palace (ISBN 978-0062468741) is a historical fantasy that centers around a golem and a jinni living in New York in the early 20th century. The Triangle Shirtwaist Manufactory fire occurs as an event that affects multiple characters in the novel.

Meet too [edit]

- 2012 Dhaka garment mill fire, a similar burn in Bangladesh

- 2013 Dhaka garment factory collapse, the deadliest garment-factory disaster in history

- International Women's Twenty-four hour period

- List of disasters in New York Urban center by death toll

- Listing of fires

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration

- Rhinelander Waldo, Northward.Y.C. Fire Commissioner in 1911

References [edit]

Notes

- ^ a b c "The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire". OSHA . Retrieved June ten, 2015.

- ^ "Sweatshop Tragedy Ignites Fight for Workplace Safety". APWU. February 29, 2004. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ Kosak, Hadassa. "Triangle Shirtwaist Burn". Jewish Women's Archive . Retrieved June 11, 2019.

- ^ Stacy, Greg (March 24, 2011). "Triangle Shirtwaist Burn down Marks a Sad Centennial". Online Journal. Archived from the original on May xviii, 2011. Retrieved June eleven, 2019.

- ^ Von Drehle, David. "List of Victims". History on the Net . Retrieved November 28, 2012.

- ^ "23 Washington Place, Manhattan" New York City Geographic Data System map

- ^ Gale Harris (March 25, 2003). "Brown Edifice (formerly Asch Building) Designation Report" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 7, 2012. Retrieved February 6, 2012.

- ^ Lange 2008, p. 58

- ^ a b c d Lifflander, Matthew L. "The Tragedy That Changed New York" New York Archives (Summer 2011)

- ^ "Triangle Waist Visitor". Sandbox & Co. Retrieved Feb 4, 2022.

- ^ von Drehle, p. 105

- ^ CPI Inflation Calculator United States Bureau of Labor Statistics

- ^ a b c von Drehle, p. 118

- ^ Stein, p. 224

- ^ a b von Drehle, pp. 162–63

- ^ Stein p. 33

- ^ von Drehle, p. 119

- ^ von Drehle, p. 131

- ^ von Drehle, pp. 141–42

- ^ Lange, Brenda. The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire, Infobase Publishing, 2008, p. 58

- ^ "The Triangle Fire of 1911, And The Lessons For Wisconsin and the Nation Today". The New Republic. March 12, 2011. Retrieved July 1, 2021.

- ^ Kosak, Hadassa (December 31, 1999). "Triangle Shirtwaist Fire". Jewish Women's Archive . Retrieved August 1, 2021.

- ^ Marrin, Albert (2011). Flesh and claret so cheap : the Triangle fire and its legacy. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN978-0-375-86889-iv. OCLC 635461169.

- ^ PBS: "Introduction: Triangle Fire", accessed March 1, 2011

- ^ Hall, Angus (ed.) (1987) Crimes of Horror Reed Editions. p. 23 ISBN 1-85051-170-v

- ^ von Drehle, pp. 143–44

- ^ von Drehle, p. 157

- ^ von Drehle, p. 126

- ^ Shepherd, William Grand. (March 27, 1911). "Eyewitness at the Triangle". Retrieved September 2, 2007.

- ^ Waldman, Louis (1944). Labor Lawyer . New York: East.P. Dutton. pp. 32–33. ASIN B0000D5IYA.

- ^ Staff (March 26, 1911) "141 Men and Girls Die in Waist Factory Fire" The New York Times. Accessed December 20, 2009.

- ^ Staff (March 26, 1911). "New York Burn Kills 148: Daughter Victims Leap to Expiry from Mill" (reprint). Chicago Lord's day Tribune. p. i. Retrieved October 3, 2007.

- ^ a b c d Berger, Joseph (Feb 20, 2011). "100 Years After, the Gyre of the Dead in a Factory Fire Is Complete". The New York Times . Retrieved Feb 21, 2011.

- ^ a b von Drehle, passim

- ^ Staff (March 26, 1997) "In Memoriam: The Triangle Shirtwaist Burn down" The New York Times

- ^ "The Triangle Factory Fire". The Kheel Center, Cornell University.

- ^ "98th Ceremony of the Triangle Shirtwaist Mill Fire". Archived March 30, 2009, at the Wayback Machine New York Urban center Burn Department.

- ^ "Labor Department Remembers 95th Ceremony of Sweatshop Fire". Archived March 5, 2011, at the Wayback Machine U.Due south. Department of Labor.

- ^ Stein, passim

- ^ von Drehle, pp. 271–83

- ^ von Drehle, pp. 155–57

- ^ Stein, p. 100

- ^ Dwyer, Jim (March 31, 2009). "On Staten Island, A Jewish Cemetery Where All Are Equals in Expiry". The New York Times.

- ^ "HFBA Timeline". Archived from the original on February 9, 2009. Retrieved March 26, 2009.

- ^ "Evergreens Cemetery". Archived from the original on June 3, 2009. Retrieved May 28, 2009. Evergreens Cemetery reports that there were originally 8 burials, one male and vi females, forth with some unidentified remains. One of the female person victims was afterwards identified and her body removed to another cemetery. Other accounts do not mention the unidentified remains at all. Rose Freedman was the last living survivor of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Burn. (1893–2001)

- ^ Swanson, Lillian (April 8, 2011). "A Grave Mark Unveiled for Six Triangle Fire Victims Who Had Been Unknowns". The Jewish Daily Frontward.

- ^ Blakemore, Erin (March 25, 2020) "How a tragedy transformed protections for American workers" National Geographic

- ^ Stein p. 158

- ^ von Drehle, p. 220

- ^ "Triangle Owners Acquitted By Jury"

- ^ Drehl, David Von (December 20, 2018) "No, history was non unfair to the Triangle Shirtwaist manufactory owners" The Washington Post

- ^ Linder, Douglas O. (2021) "The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire Trial: An Business relationship" Famous Trials

- ^ "Shirtwaist Kings " PBS

- ^ Hoenig, John M. "The Triangle Fire of 1911", History Mag, April/May 2005.

- ^ Greenwald, Richard (2002). "The Burning Building at 23 Washington Place': The Triangle Fire, Workers and Reformers in Progressive Era New York". New York History. 83 (1): 55–91. JSTOR 23183517.

- ^ Schneiderman, Rose. "We Have Found You Wanting" (reprint).

- ^ Jones, Gerard (2005). Men of Tomorrow . New York: Basic Books. ISBN978-0-465-03657-8.

- ^ Downey, Kirsten. The Woman Behind the New Deal. Nan A. Talese, 2009 pp. 33–36[ ISBN missing ]

- ^ Staff (October xi, 1911) "Seek Way to Lessen Factory Dangers", The New York Times

- ^ "Robert Ferdinand Wagner" in Dictionary of American Biography (1977)

- ^ Slayton, Robert A. (2001) Empire Statesman: The Rising and Redemption of Al Smith New York: Gratuitous Press. ISBN 0684863022

- ^ Staff (October 14, 1911) "Factory Firetraps Constitute past Hundreds" The New York Times

- ^ Greenwald, Richard A. (2005) The Triangle Fire, the Protocols of Peace, and Industrial Commonwealth in Progressive Era New York Philadelphia: Temple University Press, p. 128

- ^ Staff (March 19, 2011) "Triangle Shirtwaist: The nativity of the New Deal" The Economist p. 39.

- ^ "At the State Archives: Online Exhibit Remembers the Triangle Shirtwaist Burn down" New York Athenaeum (Summertime 2011)

- ^ American Society of Safety Engineers (2001). "A Cursory History of the American Society of Safety Engineers: A Century of Safety". Retrieved March 20, 2011.

- ^ "Rose Freedman & the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire". Retrieved December 16, 2020.

- ^ a b Martin, Douglas (February 17, 2001). "Rose Freedman, Last Survivor of Triangle Fire, Dies at 107". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June eleven, 2019.

- ^ Staff (September 16, 2019) "Senator Elizabeth Warren Speech in Washington Foursquare Park". C-Bridge. Terminal visited September 22, 2019.

- ^ Greenberg, Sally and Thompson, Alex (September sixteen, 2019) "Warren, in NYC rally, casts campaign equally successor to other women-led movements". Pol

- ^ Krieg, Gregory (September 16, 2019) "Warren promises to take populism to the White House in New York Metropolis speech" CNN

- ^ a b c Greenhouse, Steven. "City Room:In a Tragedy, a Mission to Think" New York Times (March 19, 2011)

- ^ Jannuzzi, Kristine. "NYU Commemorates the 100th Anniversary of the Triangle Shirtwaist Mill Fire". NYU Alumni Connect (January 2011) on the New York Academy website

- ^ Solis, Hilda L. "What the Triangle Shirtwaist fire means for workers at present" Washington Post (March xviii. 2011)

- ^ "Participating Organizations" Think the Triangle Fire Colition

- ^ "Chalk website". Streetpictures.org. March 25, 1911. Retrieved August 7, 2013.

- ^ Molyneux, Michael (April 3, 2005) "City Lore: Memorials in Chalk" The New York Times

- ^ Fouhy, Beth. "NYC marks 100th anniversary of Triangle fire" Associated Printing (March 25, 2011) on NBC News

- ^ Safronova, Valeriya and Hirshon, Nicholas. "Remembering tragic 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist inferno, marchers overflowing Greenwich Village streets" New York Daily News (March 26, 2011)

- ^ "Bells" on the Remember the Triangle Burn Coalition website

- ^ Transciatti, Mary Anne (March 24, 2022). "The Odyssey of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire Memorial". Labor and Working-Class History Association/Duke University. Retrieved April three, 2022.

- ^ Greenhouse, Steven. (December 22, 2015)"$1.5 Million Land Grant to Pay for Triangle Fire Memorial" The New York Times

- ^ Trasciatti, Mary Anne. https://www.lawcha.org/2022/03/24/odyssey-triangle-fire-memorial/

- ^ "Those Who Know Don't Tell". Retrieved February 18, 2011.

- ^ "Triangle Burn down". PBS . Retrieved February 19, 2011.

- ^ Hale, Mike (February 27, 2011). "Triangle Fire Remembered on PBS and HBO". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ Hardbarger, Bryan (August 23, 2011). "'Warehouse 13: Past Imperfect' – Recap". ScienceFiction.com . Retrieved May i, 2020.

- ^ Staff (August 8, 2019) "The Fire of a Movement" PBS

- ^ "Yiddish Penny Songs: Dos lid fun nokh dem fayer fun di korbones fun 33 Washington Place".

- ^ "Thanks for the Ether – Rasputina". Allmusic.

- ^ "Meyerowitz, David". Milken Archive of Jewish Music . Retrieved January 6, 2022.

- ^ Over the Edge at AllMusic

- ^ Wirewalkers and Assassins at AllMusic

- ^ Staff (March 30, 2011). "Commemorating the 100th Anniversary of the Triangle Shirt Waist Fire". Across the Pale. WBAI. Archived from the original on March 24, 2018. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ Staff (Jan 25, 2019). "Julia Wolfe: Fire in my mouth (2018)". G. Schirmer, Inc. Retrieved Jan 26, 2019.

- ^ Tommasini, Anthony (January 25, 2019). "Review: With Protest and Burn down, an Oratorio Mourns a Tragedy". The New York Times . Retrieved January 26, 2019.

- ^ Reid, Kerry (May 8, 2011). "Defiance in 'Ismene', 'Slaughter City'". Chicago Tribune . Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ^ Donaldson, Erin (March 15, 2010). "Dark Humor in 'Slaughter City' Emphasizes Industry Ills". The Daily Californian . Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ^ Lefkowitz, David. "OOB's DTW Runs Out of Birdseed, April two" Archived October 20, 2012, at the Wayback Motorcar. Playbill.com

- ^ Geselowitz., Gabriela (September 1, 2017). "Get Gear up for the Revival of a Musical You've Probably Never Heard of From the Author of 'Fiddler'". Tablet . Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ "1 Hundred Forty-Six: A Moving Memorial to the Victims of the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire" on the Remember the Triangle Fire website

- ^ "Sparks" Theatro Cargo Stagione 2015/16 website

- ^ "Triangle". Curtis Moore . Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ Scrutchfield, Lori; Nelson, Cary. "On "Shirt"". Modern American Poetry. Southern Illinois Academy. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ "Victory Party, by Geoff Berner". Bandcamp . Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ Brocken, Michael (January 28, 2013). The British Folk Revival: 1944–2002. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 276. ISBN9781409493600.

Bibliography

- Argersinger, Jo Ann E. ed. The Triangle Burn: A Brief History with Documents (Macmillan, 2009). xviii, 137 pp.

- Stein, Leon (1962). The Triangle Fire. Cornell University Press. ISBN978-0-8014-8714-9.

- von Drehle, David (2003). Triangle: The Fire That Changed America. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press. ISBN978-0-87113-874-3.

Further reading

- Auch, Mary Jane (2002). Ashes of Roses. Henry Holt Books for Young Readers. ISBN978-0-8050-6686-ix.

- Chernoff, Alan. "Remembering the Triangle Fire 100 years subsequently". CNN/Money (March 25, 2011)

- Haddix, Margaret Peterson (2007). Insurgence. Simon & Schuster Children'due south Publishing. ISBN978-1-4169-1171-5.

- Kolen, Amy (Leap 2001). "Burn". The Massachusetts Review. 42 (i): 13–36. JSTOR 25091716.

- Sosinsky, Leigh (2011). The New York City Triangle Mill Burn. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-7403-5

External links [edit]

Full general

- Chronology of events

- "Triangle Manufacturing plant Burn down", Cornell Academy Library

- List of names of victims at Cornell University Library site

- Triangle Fire Open Archive

- Booknotes interview with David Von Drehle on Triangle: The Fire That Changed America (October 5, 2003)

- Triangle Burn – An American Experience Documentary

Contemporaneous accounts

- "Eyewitness at the Triangle"

- 1911 McClure Magazine article (see pages 455–483)

Trial

- Complete Transcript Of Triangle Trial: People Vs. Isaac Harris and Max Blanck

- "Famous Trials: The Triangle Shirtwaist Fire Trial"

- 1912 New York Courtroom tape (run into pp. 48–fifty)

- Witnesses Who Testified at the Trial

Manufactures

- "Triangle Shirtwaist Manufactory Edifice", National Park Service

- "Remembering the Triangle Fire", The Jewish Daily Forward

- "Coming Full Circle on Triangle Factory Burn", The Jewish Daily Forward

- "The Triangle Shirtwaist Fire: The fire that changed America", Failure magazine

- New York, NY Triangle Shirtwaist Fire Disaster, Mar 1911 at GenDisasters.com.

- Remembering Triangle, Jacobin Magazine

Memorials and centennial

- Recollect the Triangle Burn down Coalition 1911–2011

- Conference: "Out of the Smoke and the Flame: The Triangle Shirtwaist Burn down and its Legacy"

- CHALK: annual community commemoration

- "City of Memory: Bong Ringing on the Triangle Fire"

- Rosenfeld'due south Requiem, a verse form almost the victims of the fire by Morris Rosenfeld kickoff published in The Jewish Daily Forward on March 29, 1911

- Triangle Returns. Institute for Global Labour and Man Rights, March 22, 2011

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Triangle_Shirtwaist_Factory_fire